The Business of Food: The State of the Industry

Friday, November 4, 2016

Associate Professor and John and Bruce Mooty Chair in Law and Business Paul Vaaler agrees that technology is king. “Ag is high-tech in the 21st century. Being an ag producer is a high-technology operation,” he says. “Land O’Lakes is not just selling commodities like butter. It is involved in sophisticated nutrition preparation. That’s high technology that has years in basic research and legal work in terms of patents and licensing the properties.”

Vaaler, who recently participated in an agribusiness roundtable on WCCO Radio with Professor Michael Boland of the Department of Applied Economics and the director of the Food Industry Center as well as Minnesota AgriGrowth Council Executive Director Perry Aasness, said food and ag products are often in battle for the market, not within it. “That means you have to be prepared to manage products and services that are going to have really high highs and low lows. They are dynamically competitive.”

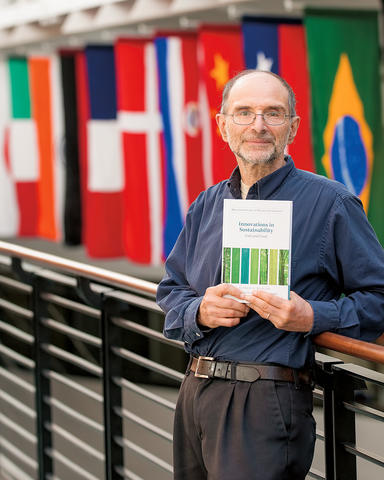

Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship Professor Alfred Marcus’ recent book, "Innovations in Sustainability: Fuel and Food," looks at how competition in the marketplace effects a company’s willingness to adopt sustainable innovations. The book has chapters on such food companies as General Mills, Kellogg’s, Coke, PepsiCo, Whole Foods, Walmart, Monsanto, and DuPont, and in studying them, Marcus gleaned much about the state of the industry today and where it may be going.

“What we have globally is a situation where we’re producing more calories than we ever had per person on less land that has ever produced these calories,” he says. “What we have essentially is not a situation of massive malnutrition, although that certainly exists, but of seven billion people, two billion are undernourished and two billion are overnourished, overweight, and obese.”

This affects the food industry because food is increasingly inexpensive. It’s becoming a commodity.

“There are many factors for this. One of them is, in the U.S., the use of corn for ethanol has been reduced, so the price of corn has been going down,” he says. “And there’s generally lower commodity prices. There have been good crop yields and harvests in the last couple of years.”

Where prices have gone down, one would think it would be a good thing. But it’s not good for seed companies. DuPont and Monsanto are both in the midst of very radical restructuring.

“Sometimes in order to succeed you have to figure out how to strengthen something you’re not particularly good at."

-Sean Walker, Senior Vice President of General Mills

“Both had a similar business model. Both sold farmers seeds that could resist herbicides. But, genetically modified seeds are hard to sell in the European market, people are afraid of consuming these seeds,” Marcus says. “There was never any scientific evidence that they would harm anybody or most Americans would be mentally deranged by now.”

Both of these companies were betting their future on this product specifically and they both financially had a hard time. If we look at companies at the next level, like Cargill, they too have suffered financially from the same kind of issues as quantity prices are on the way down.

Changing trends cause a shift in demands

Other issues are facing food producers. “If you look at Coke and Pepsi—and you have to remember that Pepsi is the largest snack company in the world—their core products are salt, sugar, and fat,” Marcus says. “Now if you look at their global sales growth in sugary sodas, it’s been almost minimal. There’s been a substantial decline in U.S. sugary soft drinks.”

These companies are really facing a strategic conundrum of where to go next. What has sustained them in profit and revenue is not the same as it had been in the past.

“It compels them to innovate and go beyond the idea of introducing diet soda to diversifying the products they sell—selling different beverages, teas, fruit juices, energy drinks, and bottled water,” Marcus says.

To chase consumers, many companies have been outright buying healthier and more nutritious brands. Greg Page, the recently retired Cargill CEO, says consumers are also interested in what’s behind the food. “We have people looking for ‘story food.’ Who raised it, the size of the farm it came from, and what kind of water resources are being used,” he says. “And there’s avoidance when you look at packages. We used to feature what food did contain and what nutrients it brought us. Now marketing claims what isn’t present. No added sugars, gluten free. To me, it’s an exciting time, but a difficult time for packaged good companies because there are so many substreams flowing through the food system.”

But of lot of these acquisitions don’t work out as well as planned. When Sean Walker, a senior vice president at General Mills and president of its Latin American operations spoke at the Carlson Global Institute’s Global Matters event in April, he said companies that do not execute things that leverage its strengths will most likely fail. In his talk, “Achieving Growth in Challenging Markets,” Walker said companies need to better understand their strengths and opportunity areas and know how to play them.

“Sometimes in order to succeed you have to figure out how to strengthen something you’re not particularly good at. But you’ve got to know those things before you start heading down the road,” Walker says. “Understanding what you’re good at, what you’re not, what your capabilities are and what they’re not, is the key to success, particularly in emerging markets.”

For example, Kellogg’s bought Kashi, a California-based whole grain cereal company in 2000. Initially, the acquisition was brought to corporate headquarters in Battle Creek, Michigan and it subsequently went into decline. “When Kellogg’s took it over and tried to absorb it, the company hit a dead end,” Marcus says. “For the standard, traditional food companies, they have acquired more healthy and nutritious brands, but they need to integrate these brands into what they did historically.”

A couple of key questions (and answers)

This is a period of great turbulence for major food companies as their traditional growth path has hit a dead end, Marcus says. “Say you are a Pepsi. You can buy snack companies throughout the world, and that is one avenue for growth—the same kinds of products that have given you success before.” But is it sustainable?

“Coke is much more a global company than an American company, but even globally they have to make choices,” Marcus says. “Are they going to stress the products they used in the U.S. or are they going to find local brands which they buy? In an ideal world, a company like Coke would like to sell the same one thing everywhere in the world. Simplify their product, simplify their advertising. It’s a problem that is particularly acute in the food business right now. Demand is very diversified.”

How best to meet these challenging demand? Page has an idea.

“I see an enormous role for business schools to train the people to have the skills to determine what people really want and translate that into marketing plans and products,” he says. Boland agrees. “Organizations can teach people the specifics of the institutions, but it helps to have some broad exposure to an industry,” he says. “The strategy being carried out by food companies is based on strategic concepts. It’s similar across industries.”

It may not at first seem obvious that agriculture and a school of management are a natural pairing, but it turns out it may be the most synergistic pairing of all, especially for the Carlson School.