The Business of Food: A Staple of Minnesota

Friday, November 4, 2016

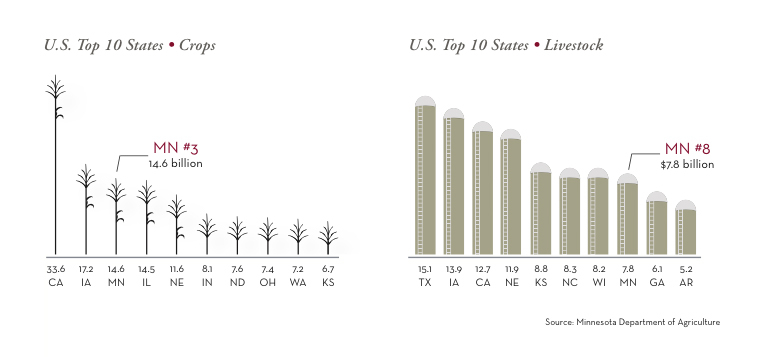

Minnesota tops the charts when it comes to ranking the states across several agricultural dimensions. The Minnesota Department of Agriculture notes that the state ranks third in the nation in agricultural cash receipts at $14.6 billion. We are number one in sugarbeets, number two for processed sweet corn, oats, and wild rice; and number three in soybeans, spring wheat, and dry beans. Our first-place ranking in turkey production and second-place in hogs earns us the eighth slot nationally in livestock at $7.8 billion.

Agriculture and food are the state’s number-one export at $8 billion. Machinery exports, in second place, are only half that. Actually, agriculture counts for more than one-third of all Minnesota merchandise exports, making this state the fourth-largest food/ag exporter in the union. And our ag value is increasing—in 2000, ag exports were only $2.3 billion.

Six of the 17 Fortune 500 companies headquartered in Minnesota are food related: CHS, Supervalu, General Mills, Land O’Lakes, Hormel Foods, and The Mosaic Company. Cargill is ranked number 1 on Forbes’ list of America’s largest private companies—and that is among all industries. With the exception of Austin-based Hormel, all of these companies are in the Twin Cities area. Is it safe to say that the Twin Cities could be considered the “Silicon Valley of Food?” Does such an appellation have merit? Does it make sense? And what is the role of a business school in making this happen?

“All the ingredients are there to create that innovation ecosystem,” says recently retired Cargill CEO Greg Page, who is now an Executive Leadership Fellow at the Carlson School. “If you look at how things have evolved in other industries, there is a certain positive network effect of being in a place where those skill sets are residing. But are we there yet?”

Page warns that although we have the ingredients to be preeminent in the food/ag space, there are aspects to be thought about long and hard and decisions to be made. “We have to think about what claims we are going to make—to pick some places where we are advanced to begin with and likely to supply employment,” he says. “The trick is to map out where we can be great, instead of saying ‘from the seed to the tabletop, we’re going to be preeminent.’ That’s a pretty bold presumption to assert about ourselves.”

Professor and Edson Spencer Endowed Chair in Strategy and Technological Leadership Alfred Marcus points out that Minnesota is built on its agricultural prominence. “We’re in the middle of the agricultural heartland and ag is the core foundation of the Twin Cities, the state, and the economy. In Chicago, the core foundation is butchering and selling meat, but our market is milling and selling grain. We’ve cornered that market,” he says. “Overall, food is a foundation for our economy. All the other great industries have built up around it. For any economy to develop, you have to have agriculture to feed your people so they can head to the cities to make steel. That’s how the Industrial Revolution started—it began with agriculture.”

Creating harmony between industry, agriculture, and science

While the Industrial Revolution started with agriculture, agriculture now needs the help of industry to stay healthy. Jim Prokopanko, retired president and CEO of The Mosaic Company and now a Carlson School Executive in Residence, once put the issue in its broadest terms: “The challenge remains to feed more than nine billion people by the middle of this century, and to accomplish this without harming the environment—especially our increasingly scarce land and water resources.”

Enter science. “A lot of these things are going to start in science. Science and engineering are big drivers in these things,” says Professor Michael Boland of the Department of Applied Economics and the director of the Food Industry Center. “Business development requires public/private cooperation. In any city where you have land grant universities like the University of Minnesota, you find many examples of these partnerships. For example, there’s been a high degree of public/private cooperation in industries such as dairy, apples, and wine and addressing state issues such as invasive species, improving water quality and soil productivity, pollinators, and similar topics so there’s already a hub started here.”

Marcus agrees, pointing to Norman Borlaug as an example. “He’s probably the most important scientist of the last 50 years of the 20th century,” he says.

Borlaug, who was awarded the Nobel Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Congressional Gold Medal, earned his MS and PhD degrees from the University of Minnesota. Working with combining different plant seeds, he successfully developed varieties of high-yielding wheat. Imported into India and Pakistan, which were suffering severe food shortages, these plants helped both countries become self-sufficient in wheat production. Borlaug was subsequently heralded as the father of the Green Revolution and the “Man Who Saved a Billion Lives.”

“We’ve always been a source of innovation in the science of agriculture and productivity enhancement and it has a global reach of immense proportions,” Marcus says. This global reach, however, sometimes has local impacts.

Between a rock and a hard place

“People travel and see the high quality of the produce in other countries and wonder why we can’t have the same level of quality in the U.S.,” Marcus says. “This puts a great burden on the retail outlets to lower the amount of food that they have to throw out by better understanding their customer and their customers’ consumption habits.”

The retailer is stuck between the rock of low prices and the hard place of the appearance of quality. “In the Twin Cities we have a great laboratory of food retailers competing with each other,” Marcus says. “There is probably more diversity in our choices than in any other metro area in the U.S., but none has found in my opinion the absolutely perfect formula.”

Consumers want their produce to be fresh, but the produce is often traveling vast distances and it sits in the supermarket for long periods of time, hurting its taste and nutritional value. “Supply chain efficiencies based on data analytics and a better understanding of inventory turns have the promise to improve this process,” Marcus says.

In the food industry, there is an entirely linked value chain of inputs, transportation, and retail. Consumers are increasingly demanding to know where their food came from and how it got to their retail outlet. “There are vast changes at each stage in this chain,” Marcus says. “Farmers, as always, are interested in the most output for the least input and this means increasingly understanding nearly each square centimeter of where the food is grown and how to adapt the seed, the water, and the chemicals that are used in that centimeter. The technology now exists to do this kind of precision agriculture and some of it has come from the University of Minnesota.”