In Pursuit of Continuous Improvement

Friday, April 2, 2021

BY DARA MOSKOWITZ GRUMDAHL

What kind of person dedicates their lives to improving supply chains and lean production? A person exactly like Rachna Shah, who was recently promoted to full professor of Supply Chain and Operations at the Carlson School.

Improved supply chains—everybody wants them! Why? For more affordable products, more profitable and stable employers, less carbon in the atmosphere, and a zillion other reasons. But, in order to get improved supply chains, someone’s got to devote a life to their study. What kind of person would take that on? Meet Rachna Shah, the newly minted full professor of Supply Chain and Operations at the Carlson School of Management, and please know: Lean production, better supply chains, fewer recalls, and continuous improvement are all passions she’s been refining her entire life.

So much of what I teach comes down to matching supply with demand. Waste, when I was growing up, was abhorrent.

It all started in New Delhi, where Rachna was born, the first of two children, the most prestigious of all positions, descending from a family of prosperous businessmen on her father’s side, and prestigious academics and government officials on her mother’s. She grew up in old Delhi, in a haveli owned by her family for, she guesses, at least six or seven generations. A haveli is a traditional Indian home, somewhere between a house, an apartment building, and a castle: multi-storied, with pillared balconies built around an internal courtyard. Inside, all the families of her grandfather and his brothers lived in rooms off that main courtyard. Shah’s family lived in an area that opened onto a roof scattered with potted plants, where she could see historic mosques and tombs on every side. “This was a very common way to grow up in walled cities in north India,” protests Shah, when I say it must have been very beautiful. As a little kid she tore around inside the haveli with her little brother and her little cousins, playing dolls and tag.

Her paternal grandmother ran everything in the haveli with exacting standards and an eye toward what Shah now sees as a carefully controlled supply chain feeding the lean production that created the extended family’s meals. Ingredients were sourced from trusted suppliers—mustard oil from a grower the family knew, butter from a milkman who worked directly with the family. And rarely, if ever, did the family buy wheat flour—only whole grain wheat, to be milled as needed under direct supervision of someone in the house.

“It was a different way of life,” laughs Shah. “You did not just buy cookies, for instance. Most people had one bakery they went to, and you would take your own flour you had made, bring your own butter maybe from your own farm, and then someone from your house would sit there and watch the whole process to make sure you got exactly what you wanted, high quality.”

In fact, quality control was such a significant family value in her childhood that young Rachna was given a toy grain mill as part of her preschool kitchen playset. Refrigeration wasn’t common at the time, and fruit and vegetable vendors would bring carts to the haveli every day, for grandmother to inspect their wares. She’d pick summer fruits in summer, like watermelon and bananas, rainy-season fruits like berries and jambolun in the rainy season, citrus fruits in winter—to her, the idea of eating low-quality, out-of-season fruit was ridiculous.

“So much of what I teach comes down to matching supply with demand,” explains Shah. “Waste, when I was growing up, was abhorrent. You didn’t want to waste food, at all, nor buy too much. But also, hospitality requires that if someone came to visit around dinner time, you didn’t let them go without. So anyone running a household at the time had to have a very good sense of inventory, of matching supply with demand.” In the afternoons her grandmother would peel and cut the fruit, while keeping an eye on the door for young Rachna’s return—and if the driver was late, she would go out and interrogate him and find out why. Continuous improvement was needed! It is not surprising to discover that this is the history of the person businesses call on when they must figure out exactly where in the process their medical devices went wrong.

These days Shah specializes in an aspect of business called “lean.”

“What I study in lean are two high-level questions: How do firms become operationally excellent, and also, why do operationally excellent firms fail? When I teach lean, I tell my students: I can use a fancy Japanese term for everything we are about to study, and that will make it sound impressive, but it is really all common sense.”

To emphasize that core of common sense when she’s teaching Carlson School students, Shah makes sure that practical aspects are centered by assigning everyone a real-life home personal project, as well as a professional one.

“I’ve had students take on organizing their house, garage, and kitchen cabinets, using principles I’m teaching, like visualization, how you should be able to clearly see everything you need,” says Shah. “I remember one student had three young children, and in the morning everyone was running like crazy, grabbing diapers, but if there were no diapers left—now they were late. They figured out a way at night to get the kids ready, a way to pile up diapers and know when the last one was left, a system to replenish them. I asked them to keep metrics. The husband was a legal councilor for a large, local company, the wife was a busy physician. The wife called me up: ‘Due to your class we now have time to have a cup of coffee together in the morning without running like crazy to get diapers.’”

Whether you are cleaning a pot or making a car, I believe you can understand the underlying processes, and try to make things better.

Shah’s passion for continuous improvement seems to have started back in New Delhi, too. For instance, Shah recalls the many times her Catholic school uniform would come back to the house from the professional laundry, nicely pressed.

“But folded!” remembers Shah today with a laugh. “In the morning, I would see a crease, take the uniform to the place we ironed to iron it. My mother would say, ‘It just came last night, it cannot be wrinkled!’ I would say. ‘There’s one wrinkle, I can see it.’” Shah was not going before the school nuns for uniform inspection in an unimproved state.

“Whether you are cleaning a pot or making a car, I believe you can understand the underlying processes, and try to make things better,” says Shah of her improving instincts, which would, a few decades later, blossom into groundbreaking research papers. “It just so happens that many of the underlying principles I study align with my thinking—of constantly improving yourself, of doing the best you can do at whatever you do. A lot of that is my grandmother and father’s influence. I can still hear my father saying: ‘Whatever you do, you must do the absolute best you possibly can.’”

You can likely easily imagine the post-primary school years of Shah’s life: Academic star in India (earning her BA in Economics from Delhi University) continuous excellence stateside (MBA and PhD in Operations Management from the Fisher College of Business, The Ohio State University), research and publication of numerous papers. In one such paper, Shah and her colleagues studied three characteristics of lean production by collecting data from almost 2,000 manufacturing plants—namely, plant size, plant age, and union status. The conventional wisdom at the time was that old plants, small plants, and unionized plants would not be able to implement lean practices. Shah found that was definitively not true. That paper has now been cited more than 3,000 times.

“I’m not interested in things that just explain what is, in econometric terms,” explains Shah. “Is X a driver of Y? That interests me less than why does it work, when does it work, and, to less of an extent, how does it work.” If you know the why, when, and how, you can replicate it. “I find my stream of research very satisfying because most of it has practical implications.”

Shah has looked into drug manufacturing recalls, to determine that drug plant inspectors should be rotated so that they are less likely to focus on the state of prior infractions, but instead have fresh eyes for unrelated problems. She has studied what makes managers in charge of medical devices either too quick or too slow to recall problem devices, and worked to devise training to reduce those personal inclinations.

Needless to say, Shah has long used the principles of management she teaches and researches in her own home in Eden Prairie. She keeps her jars of spices near the stove in a drawer, labeled on their tops so she can see them at a glance. She keeps scissors just beside the stove, and additional scissors in strategic spots throughout the house where packages or mail might need opening. “Not wasting steps, not walking around, my kitchen is very visual and set for lean process flow,” explains Shah. “Many faculty have made fun of me for my love of processes and continuous flow when they come here for parties.”

Speaking of parties, all Carlson School folk should work on securing an invite to one of Shah’s parties. They are legendary, with the professor routinely cooking for 50 to 100, with breads, curries, and almond cookies— everything from scratch. “I love to eat, but even more I love to cook,” says Shah. “Socializing and cooking, in a big way, these are my great joys.”

Not wasting steps, not walking around, my kitchen is very visual and set for lean process flow.

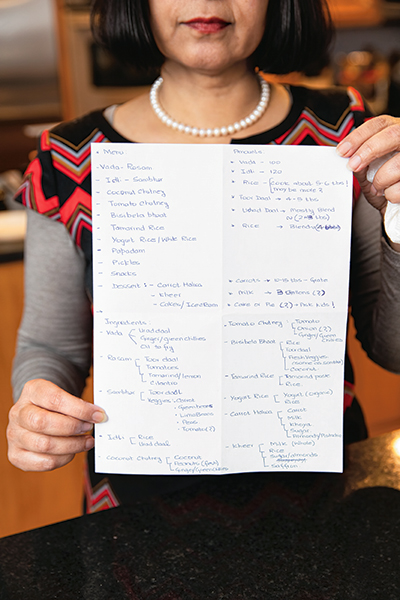

She starts out with menus, which flow to very detailed order lists. Her husband, Jatin, who does almost all the shopping, gets the ingredients. “He’s my purchasing manager as well as my sous chef,” laughs Shah. “But seriously, I could not have done the many things I do without him.” Including raising a family: Rachna and Jatin have two daughters. Tanya is finishing her residency in Milwaukee, in critical care. Rachna says, “We are very proud of her choice. It is especially relevant in this age of pandemic.” And Priyanka, their younger daughter, works for Accenture. She notes: “It is scary to see that she’s almost like me, but even better. If I could go back 15 years I’d say, ‘Make sure when you’re talking to kids, continuous improvement doesn’t sound like continuous criticism for every little thing.’ Looking back, I’d say the most important thing is to let your kids know you are there for them, no matter what.”

I ask Shah if this stream of thoughts is a good example of her continuously improving her continuous improvement—and she laughs.

“On the one hand, if I look at my whole life, it’s circuitous, there was not a major strategic plan. But on the other hand, I think of every fork in the journey of life as an opportunity, and try to do the best at whichever path I take.”

Which is how a whole life leads to improved supply chains—and continuous, continuous improvement adds up to why Rachna Shah has achieved full professorship of exactly that.