Four Social Entrepreneurs Changing the World

Monday, March 23, 2020

BY CHRISSY SORENSON

These University of Minnesota alumni are creating transformative change on a global scale.

Joy McBrien

Fair Anita

Joy McBrien’s mom, a first-grade teacher, ingrained this mantra in Joy at a young age: “A problem is a problem to solve. What’s your plan?”

For McBrien, ’11 BSB, the plan—create a world where women feel safe, valued, and respected—evolved from her own experience as a survivor of rape. For years, she was anxious, depressed, and “trapped inside her brain,” she says, reacting to the trauma. In an effort to repair and restore her healing, she channeled energy into addressing the bigger problem of sexual violence.

While at the Carlson School, she designed an international business study-abroad program in Peru—the country with the highest reported rate of domestic violence in the world. It was there, 4,000 miles from home, she says, “I found myself, both literally and figuratively.”

Part of this reawakening was inspired by Ana, aka Señora Anita—McBrien’s host mom and a beloved social worker in the town of Chimbote, Peru. Anita helped to reframe McBrien’s perspective, as did the resilient women she met while building a women’s shelter. The resounding refrain: Invest in women by providing economic and educational opportunities, creating safe spaces, and empowering women to be economically self-sufficient.

With a grasp of the problems firmly in hand, McBrien saw an opportunity to develop a longterm, sustainable plan to empower female artisans around the globe.

“Women often stay in abusive situations because of financial insecurity,” McBrien says. “When women are included in a formalized workforce, entire economies grow. When women do better, communities do better.”

When women are included in a formalized workforce, entire economies grow. When women do better, communities to better.

McBrien returned to the Carlson School three months later with a clear purpose—developing different iterations of Fair Anita, tweaking the products and the strategy. She credits academic advisor Anny Lin, professor Steve Spruth, and innovative and socially motivated classmates for helping her solidify her vision: Her business would sell affordable, trendy locally-sourced jewelry, apparel, and accessories handmade by female artisan partners. She would pay them double or triple the minimum wage and offer both health insurance and educational scholarships.

Fair Anita launched in January 2015 as one of the first public benefit corporations in Minnesota. McBrien explains that means that Fair Anita is “mission-driven, in addition to our for-profit status, and we’re legally obligated to be working to provide economic opportunities to marginalized women.”

Seed funding came from the Colonial Church of Edina, providing McBrien with the loan she needed to hit the ground running. And she ran, all right: Four years and multiple international trips later, Fair Anita hit a milestone of $1 million paid to thousands of artisans in nine countries (three in Latin America, three in Southeast Asia, three in Africa). Staff has grown to include a full-time operations manager and 10 part-time employees, with McBrien rolling up her sleeves and working alongside the team. Even after presenting a TEDx Talk and receiving numerous entrepreneurship awards, McBrien stays grounded—never losing sight of the problem or the plan: “When we invest in one another, we rise together.”

Find Fair Anita products at the Weisman Art Museum, independent retailers, art fairs, pop-up shops, breweries, and online at fairanita.com.

Leslie Grueber

Peace Corps Morocco

Leslie Grueber, ’14 BSB, isn’t OK with the status quo.

After studying abroad in Switzerland, graduating from the Carlson School, and working in the real world for three years, she became more aware than ever of disparities in gender equity.

Rather than taking a backseat, she took action.

In 2017, she applied to the Peace Corps. With a background in business and strategy consulting, experience in the Carlson School’s Women in Business organization, a genuine interest in international relations and economic development, and a sincere desire to help women, trans, and non-binary people achieve financial independence and proper economic inclusion, she was more than qualified to support gender-related work. The Peace Corps placed her in the North African country of Morocco.

We wanted to make sure the women were gaining skills and could participate and lead their own cooperative without relying on outside sources.

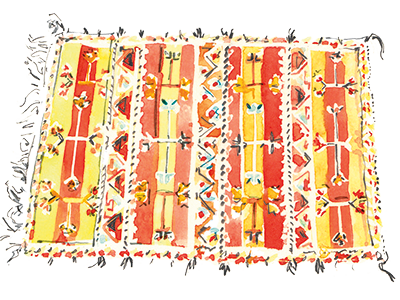

In her role focusing on gender and economic development, she worked with a women’s association in the Valley of the Roses, a small village located in the southern foothills of the Atlas Mountains. The goal? To start a weaving and sewing cooperative, “kind of like an artisan small business with a cooperative structure,” she says. She helped design an entrepreneurship curriculum in collaboration with a local counterpart. “We wanted to make sure the women were gaining skills and could participate and lead their own cooperative without relying on outside sources.”

She also served as a volunteer committee chair for the Peace Corps Morocco Gender and Development Committee (GAD), working with Peace Corps volunteers and Moroccans to develop relevant strategies and resources for addressing gender issues.

Living in Morocco allowed Grueber to see the complexities of the region—observations she would have missed had she not been immersed in the culture, which is why she advises others hoping to make a global impact to develop self-awareness and fully understand the issue before interjecting themselves.

And don’t be afraid to take a risk, she says. She has no regrets about leaving a corporate job to live in a remote Moroccan village: She learned Arabic, tried local foods, and created meaningful bonds with coworkers and neighbors. “I couldn’t walk outside my house without being offered tea by someone,” she says. Most importantly, her Peace Corps experience showed her that—just like the Arabic saying of “schwiya b’ schwiya,” or little by little—change is possible.

Now that her 27-month Peace Corps commitment has ended, her goal is to pursue a master’s degree and continue working toward advancing the cause of financial inclusion for everyone. Gender equality isn’t a women’s issue, it’s a human issue, she says.

“Our goal should be that all humans, regardless of gender identity, are afforded equitable access to opportunity and agency over their own lives, and that societal structures are not systematically stripping power from some and uplifting others based on any aspect—gender or otherwise—of a person’s identity.” She adds, “The issues we face are as multifaceted as our identities, so the solutions have to be, too.”

Sarah Pritzker

Atlas Provisions

To really experience a country, you need to experience its food. Sarah Pritzker, ’16 MBA, had enjoyed trying different foods throughout her travels in Europe and South America, but it was a flavorful seed from India that changed her life.

“I’m sitting in this classroom [while studying international business through Carlson in Bihar, India]—it’s hot, I’m tired, I’m struggling to focus. My professor hands me a bowl of seeds. Instantly, I’m hooked,” she recalls.

What she had tried was popped lotus seeds, also known as phool makhana, fox nuts, or water lily seeds—kind of like popcorn, but without the hull to get stuck in your teeth. During the remainder of her study-abroad, the seeds—puffy, flavorful, and airy—became her go-to snack. They also happen to be low-calorie, vegan, gluten-free, naturally anti-inflammatory, and high in antioxidants, magnesium, and potassium.

When Pritzker returned to Minnesota, she couldn’t track the seeds down anywhere—even on Amazon. So, she started doing some digging. Her research uncovered a detailed method of farming in India: Seeds are harvested from the water-growing lotus flower. Collected from the water floor after the pods burst open, they are then cleaned and dried in the sun. It’s farming the way it’s been done for generations, in harmony with the natural landscape. Efforts to mechanize the process have failed. “There’s so much wisdom in those ancient methods,” Pritzker says.

She also discovered a major flaw in the supply chain: The farmers were purchasing the seeds from the same traders they were selling to, perpetuating a cycle of debt. “And that’s when everything started clicking into place,” she says. Her vision: Source the seeds—paying above market rate—directly from the farmers, provide fair wages “so the farmers have a pathway to lift themselves out of poverty,” import the seeds, introduce an international food to U.S. consumers, and proudly tell the story of a socially and environmentally responsible supply chain. Second-year MBA Tanvee Singh—a native of India—proved instrumental in helping Pritzker navigate the local landscape and find quality checkers, food safety specialists, and suppliers in Bihar, as well as increase Amazon sales by more than 400 percent.

When I do reach out, I’m overwhelmed at the response. I’ve been so humbled. It really does take a village.

Thanks to the generosity of a Sands Fellowship, and by using the knowledge she gained through her MBA, lessons learned on the board of the Women’s Mentorship Program, and valuable industry connections made through the Center for Entrepreneurship, Pritzker launched Karmic Kitchens in 2016.

At first, the popped lotus seeds were sold at the Linden Hills and Northeast Farmers’ Markets and Lakewinds Food Co-op in Minneapolis. Today, you can purchase truffle salt, chocolate sea salt, chipotle-lime, or maple-caramel popped lotus seeds at a number of local grocery retailers, Amazon, and through the Atlas Provisions website. (Pritzker eventually changed the company’s name from Karmic Kitchens to the all-encompassing Atlas Provisions, should they one day expand into home goods or body-care offerings.)

As the CEO of a startup, the ambitious Carlson School alum admits that asking for help can be challenging. “When I do reach out, I’m overwhelmed at the response,” she says. “I’ve been so humbled. It really does take a village.”

The company—now seeking outside capital—is small, but preparing to grow. Pritzker has learned entrepreneurship is an endurance game. Like farmers waiting to harvest seeds from the slow-growing lotus flower, patience is part of the process.

Kate Kuehl

Mobineo

Outdated. Inaccurate. Nonexistent. Up until four years ago, those words could be used to describe the majority of land records in sub-Saharan Africa.

Kate Kuehl, the 2018 Carlson School Gary S. Holmes Center for Entrepreneurship Student of the Year and University of Minnesota graduate, has been working diligently to change that.

In 2016, she co-founded a platform called Mobineo (moh-bin-NAY-oh)—a combination of the word “mobile” and the Swahili word for land—to provide people in Eastern Africa with the necessary tools and property data to define and claim what’s rightfully theirs. The land documentation software company, used by non-government organizations, land surveyors, and land administrators, includes a digital land-surveying app, GPS, website, and database, as well as training and consulting. The end goal is to streamline the process by taking a digital approach to tracking proof-of-land ownership.

Just a year before launch, in 2015, Kuehl was in Kenya studying food systems with the Kenyan Agricultural Research Institute when a simple conversation with a local farmer lit a spark—eventually shifting Kuehl’s entire career trajectory. The conversation was focused on investments—more specifically, why more farmers didn’t invest in their land. The woman, a widower, asked Kuehl, “Why would I invest in this land if I don’t own it?” It didn’t matter that she and her husband had farmed the land together for years. He had inherited the land through his family, and because her name wasn’t on the title, she had no legal right to keep it upon his death.

The World Bank estimates that women run more than 70 percent of Kenya’s farms, yet only 10 percent of the land is documented. And according to estimates, only 1 percent of women in Kenya hold land titles in their own names, while only 5 percent own land jointly. Kuehl discovered that when title deeds did exist, it was through an antiquated paper system. If images were scanned, they weren’t uploaded into a searchable database.

Without titles, women risk losing their property, and with it, their financial stability and any hope of long-term prosperity. A title is seen as valuable collateral to obtain loans. “Land rights are fundamental to stimulating investment and economic growth,” Kuehl says.

Land rights are fundamental to stimulating investment and economic growth.

She started talking with Dave Okech, an entrepreneur from Kenya, about her idea to build a platform for surveyors, making it easier for them to do their jobs. Okech had the experience and skills to cultivate government relationships in Kenya; Kuehl had the coding knowledge to write software and the technical know-how to implement it.

When she returned to the University, she took courses in preparation of running a business. She launched Mobineo in 2016.

“We tried to take a complicated subject and make it straightforward,” she explains. So far, so good—even with a few funding hiccups.

As a student, Kuehl admired and respected entrepreneurs, inviting them to the University campus to speak, hosting workshops, and working with the Innovation Coalition to create more entrepreneurship spaces on the East Bank.

Now, she’s the one invited to speak.