Carlson School Alum Adds MBA to MD for New Strides in Surgery

Friday, April 8, 2022

BY SARAH ASP OLSON

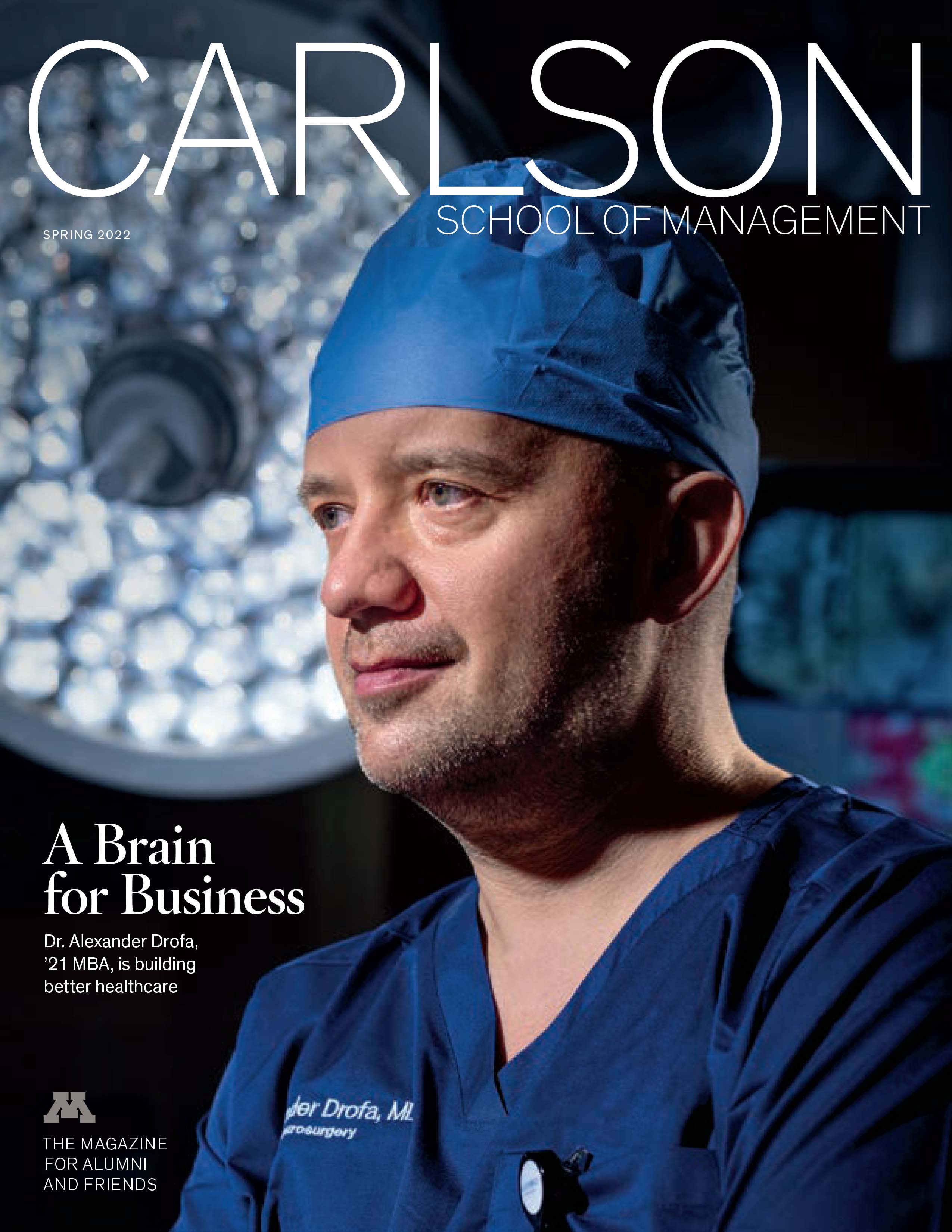

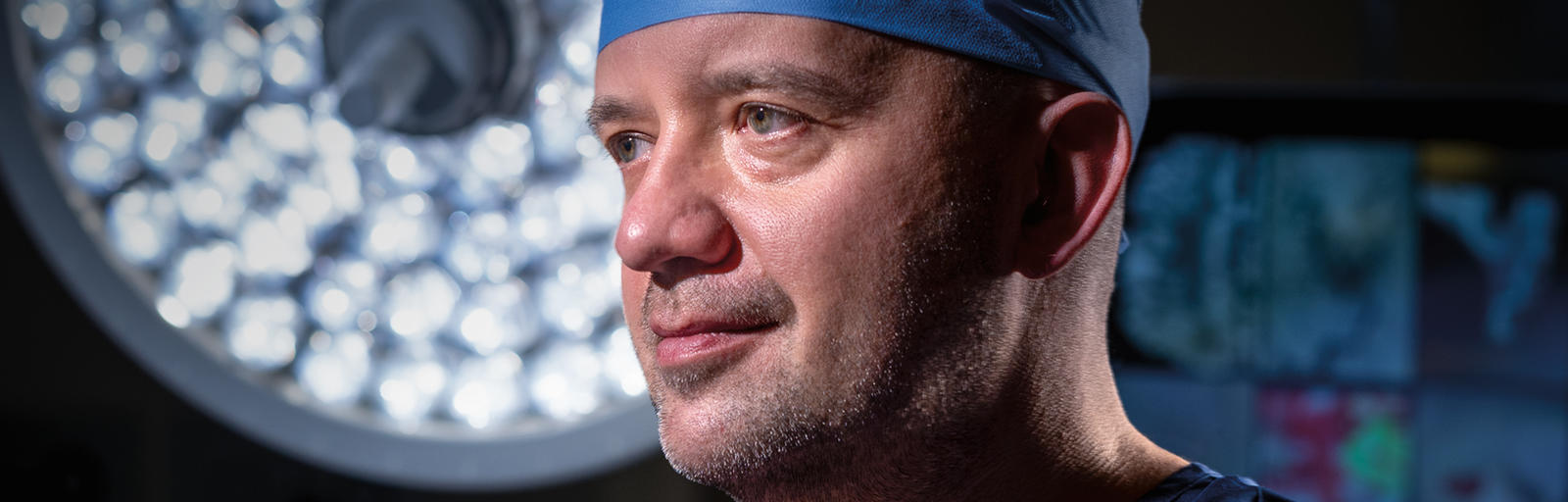

It may not be common for a surgeon at the peak of his career to head back to the classroom for another degree, but Dr. Alexander Drofa is far from common. The neurosurgeon and medical director for cerebrovascular neurosurgery at Sanford Medical Center Fargo earned his Carlson School Executive MBA in 2021 and is already putting it to good use.

Dr. Alexander Drofa was on campus at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities for one of his first immersion weeks as a student in the Carlson Executive MBA (CEMBA) program when his day job called. There was a crisis and he needed to get home. For a typical CEMBA participant that might mean a supply chain issue or a PR incident—something a CEO might be able to handle remotely. Not so for Drofa, who was called back to perform surgery at Sanford Medical Center Fargo [North Dakota]. This crisis was literally life or death.

“That speaks to his capabilities but also [his] perseverance,” says Joe Weber, Drofa’s CEMBA classmate and a SaaS operations executive to private-equity businesses. “He had to go save somebody’s life.”

While he missed a day of class, Drofa returned the next day and “didn’t lose a beat,” says Weber.

It’s one of many stories colleagues and friends tell that exemplify Drofa’s determination, persistence, and seemingly endless well of energy. Like the one about how he came to be the medical director for cerebrovascular neurosurgery at Sanford Medical Center Fargo in the first place.

“I just wanted to build.”

Drofa, who hails from Novgorod, Russia, has physician parents, so following in their footsteps was a natural fit. He chose a specialty in neurosurgery because he likes a challenge.

“Neurosurgery is one of the most challenging specialties to be trained in,” he says. “It’s not only a mental challenge; it’s a physical challenge and intellectual and technical challenge.”

After medical school, Drofa did his residency in Manitoba, Canada, and eventually accepted a fellowship at the Cleveland Clinic. When it came time to find a place to settle, Australia was on his radar, but he hadn’t considered the extent of opportunities in North Dakota.

“When you come from one of the best cerebrovascular fellowships in the world at Cleveland Clinic, you can go anywhere,” he says. “When I came to Fargo for the interview, I realized that this is a great opportunity to start practice and grow the program. There were no cerebrovascular care facilities from Seattle to Minneapolis.”

In fact, Fargo is 230 miles from the University of Minnesota Medical Center and more than 1,200 miles from more prominent neurosurgery centers on the West Coast. In between, there wasn’t much available for patients suffering stroke, brain aneurysms, or other complicated cerebrovascular issues. Drofa took it as a challenge.

“I just wanted to build,” he says.

“Prior to Dr. Drofa’s arrival in Fargo, Sanford did not have a neuro-endovascular program,” says Brittany Sachdeva, vice president of operations at Sanford Medical Center Fargo. “The majority of the patients with vascular pathology in their brain were sent out of the region and out of state for care.” But since Drofa’s arrival, the team has grown, including a second endovascular neurosurgeon, an interventional neurologist, two stroke neurologists, and three neurocritical care physicians, who respond to an ever-expanding call for care—more than 2,500 cases of various kinds of strokes in the last three years alone.

“We did everything ourselves,” he says. “We built it from scratch.”

“When cases like this come in and they’re outside of normal framework or previous experience or guidelines, you view it as a challenge. … I just do basically a technical calculation: ‘What if I do this? What if I don’t do this?’”

"Why not? Let's just try it!"

One of the first exercises Drofa and his CEMBA cohort, including Weber, were given in the first year of the program was the “lost at sea” challenge.

“It’s a typical challenge around what tools you should keep to survive if you’re lost at sea,” says Weber. The exercise is designed to promote team-building and strategic thinking. But, while most individuals get about half the items in the optimal order, “when you get a team together, they start talking about it and generally go in the wrong direction.”

As Weber recalls, Drofa got a nearly optimal sequence right off the bat, but that wasn’t the most remarkable part.

“Ours was the only [group] to actually improve beyond that,” he says. “That speaks to Alex’s ability to integrate and work well with teams. Not only did he convince us of his direction, but we were also able to improve upon that by saying, ‘If we’re going to apply the logic you’ve convinced us of, we actually see some improvements we could make.’”

Weber continues to work with his former classmate in a variety of entrepreneurial ventures outside of the healthcare space and has seen the way Drofa’s leadership skills play out in the real world.

“One of the phrases he uses is ‘Why not? Let’s just try it!’ He’s able to bring an extraordinarily high intellect to problems as well as that ability to be selfless and collaborate. The combination of those two is very rare.”

As a surgeon the “why not?” approach may feel risky, but when coupled with training, careful calculation, and risk assessment skills, it can lead to some remarkable outcomes for patients in his care.

One such example came early in Drofa’s tenure at Sanford. In 2016, a nine-day-old newborn arrived at the hospital, having suffered a stroke. It seemed like there was nothing to be done. His parents were preparing to say goodbye—until Drofa proposed they try something. He spoke with the parents, consulted with colleagues, and decided to perform a procedure that was routine in adult stroke patients, but had never been done on such a young child.

“Medicine is not necessarily [just] science. It’s also art and craft, and we do have some frameworks that we adhere to, guidelines and previous experiences,” he says. “When cases like this come in and they’re outside of normal framework or previous experience or guidelines, you view it as a challenge. Things can get very emotional. I try to take all the emotions away. … I just do basically a technical calculation: ‘What if I do this? What if I don’t do this?’”

In this case, Drofa’s calculation was straightforward: If he did nothing, the child would die. So, he was determined to try.

“Sometimes you don’t have to think about it. You just have to do it,” he says. “Nobody had done it before. There are no tools available. One had to improvise. It is like sailing across uncharted sea.”

Drofa and his team gathered the smallest devices they had on hand and were able to remove the clot and place a stent. A year after his procedure, Drofa’s young patient was alive and thriving. In an interview with ABC News just after the boy’s first birthday, his father recalled what Drofa said to him before surgery: “He said … he couldn’t deal with not doing anything.”

From Fargo to Ghana with hope

This year, Drofa is once again in the news for taking on a seemingly insurmountable challenge. He is part of a team of physicians who will attempt to separate Ghanaian twin babies, who are joined at the head.

Portions of the twins’ brains and vascular systems are intertwined. Drofa, along with a team of international surgeons and specialists, are setting out on a multistep, monthslong process to untangle them.

Jim Slack, vice president of Sanford World Clinic, was the one who first learned of the twins and presented the opportunity to Drofa.

“[Sanford World Clinic] is partnered with and supporting the Ghanaian healthcare team with expertise, strategy, and hands-on participation by Dr. Drofa in completing this multi-staged complex separation of the twins,” he says. “Sanford is the only U.S. entity participating and we are one of approximately four international partner countries participating in different stages of the separation.”

In fact, Drofa is the only U.S. surgeon who will be physically operating on the twins. This, he says, is partly due to a shared mindset among Sanford World Clinic, the Ghanaian team, and himself.

“The challenge for [the Ghanaian team] was they approached many U.S. institutions … but then discussion would become, ‘Send this patient to us. We’ll pay for everything. We’ll do it. We don’t want you to get involved,’” he says. “Our mentality here is still very much from scratch, based on we built one of the best stroke programs in the country. … So this pulls on our mentality to do things locally, make sure we can do it safely. … So we said, ‘Yeah, you guys should do it there. We’ll come and help you. If you need us, we’ll step in, but you guys should be doing it.’”

Drofa made his first trip to Ghana in December 2021, where he reviewed the case and mapped out the consequences of each surgical action and how to “de-risk this whole process for these particular patients.”

And while Drofa’s involvement as the only U.S. surgeon on the team is notable, and speaks well of his abilities and his institution, he sees himself as “just a part of the team.”

“My part is pretty small, but overall, it’s just an honor to be a part of this.”

It’s this mentality—part of a team that is building something and doing something extraordinary—that drives Drofa in his day-to-day work in Fargo (which he now calls “a hidden gem”).

“That’s what excites me,” he says. “We’re building everything from the ground up, and we are part of a big organization that provides top-of-the-line healthcare for the patients, and that surpasses many, many healthcare systems in the world. That’s very exciting, being a part of this.”

MD + MBA = Unstoppable

Why add an MBA on top of an MD and successful career in medicine?

For Dr. Alexander Drofa, it’s all about understanding the big picture.

Carlson Magazine: What prompted you to get an MBA?

Alexander Drofa: I like the challenge. I like to understand the big picture. I like to push things further as much as I can because that’s what drives me. That’s why the Carlson School of Management was the perfect choice because that’s what the executive program does. … I realized also in my role as a healthcare leader, I’d like to understand the financial aspect of healthcare, the mechanics and revenue structures. I’d like to understand how people who lead the organization think.

CM: Why the Carlson School?

AD: It’s in the top three programs in the world right now based on the most prestigious ratings. That’s what attracted me. I got into several business schools, but I went into this because of their strong ratings. The teaching there was very hands on, very tailored to my needs, and not only made me a better businessperson, but a better administrator, too.

CM: How has your CEMBA experience shown up in your practice?

AD: It’s definitely helped me a lot, creating more value for my work and specifically for … this particular case with Ghana, I think not having this knowledge, I would be just a guy, like a technical guy, like a craftsman, who comes in and helps them out, but I brought so much more value to this by having the business knowledge and having a bird’s-eye view on the whole process, not just a little technical part.